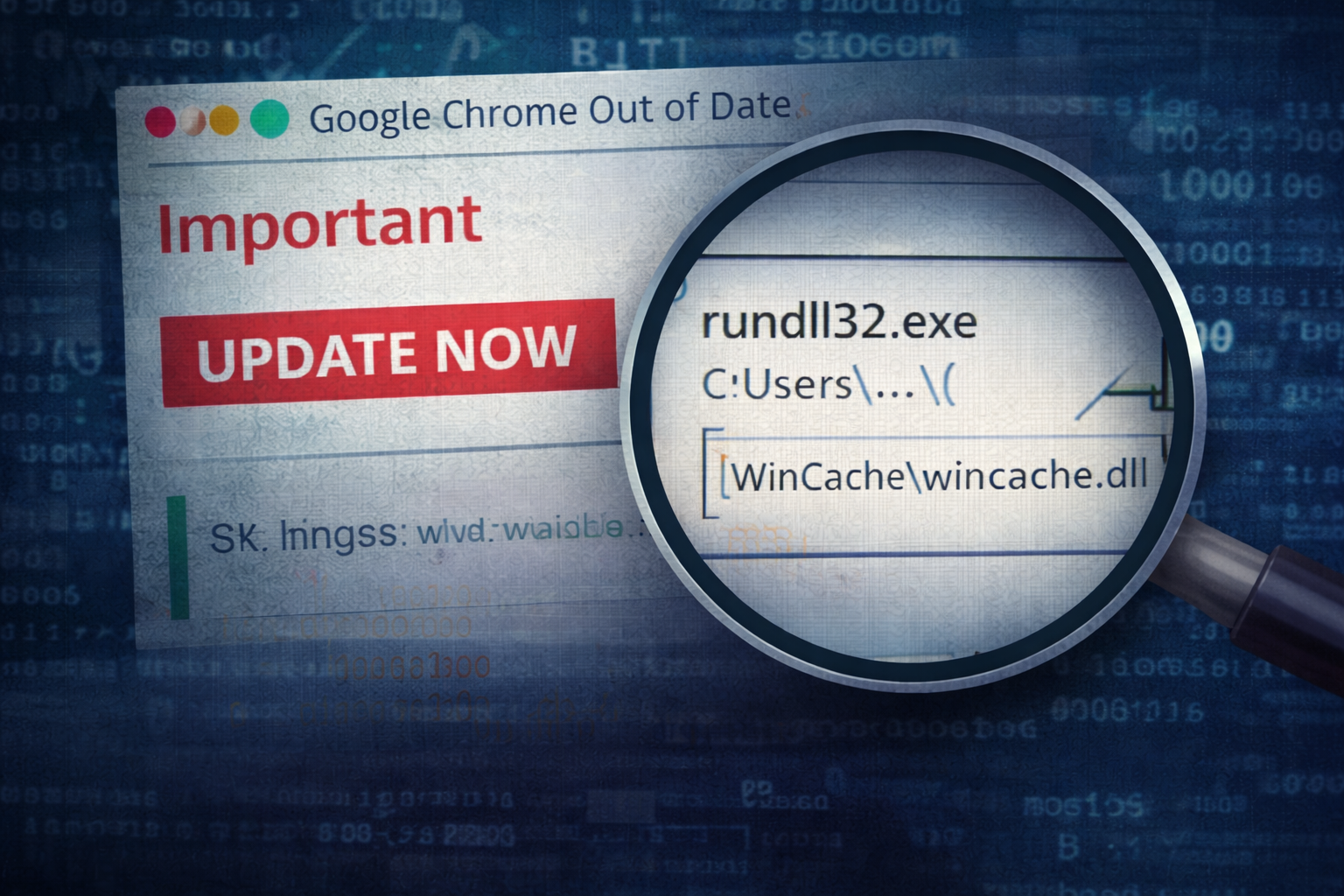

Fake Browser Update → Loader Execution in Minutes

A user clicks what looks like a routine browser update. Within minutes, a ‘legit’ installer chain pivots into rundll32 execution, persistence via scheduled tasks, and outbound beaconing to fresh infrastructure. This casefile walks through the investigation flow, the key artifacts that mattered, and the practical detections that catch the pattern early.

Scene-setting: the “normal” update prompt

This one starts the way so many real intrusions start: with something that looks boring.

A user reports a pop-up claiming their browser is out of date. It’s styled like a familiar update banner, uses the right product name, and pushes urgency just hard enough to get a click.

No exploit. No zero-day. No “hacker movie” indicators.

Just a normal user doing what they think is the right thing: updating software.

And that’s why it works.

What triggered the investigation

A single alert came in from endpoint telemetry:

- An installer ran from the user’s Downloads directory

- Within minutes, rundll32.exe executed a DLL from a user-writable path

- A new scheduled task appeared shortly after

- Outbound HTTPS connections started to a domain we hadn’t seen before

On its own, any one of those might be noise. Together, it reads like a classic “fake update → loader chain”.

Timeline: what happened (high-signal version)

You don’t need a 4-page timeline to understand this pattern. You need the pivot points.

1) User execution from Downloads

A file with an “update-ish” name is launched from:

C:\Users\<user>\Downloads\

This matters because “fake update” campaigns love:

- Downloads

- Temp directories

- User-writable locations that bypass “Program Files” friction

What to capture:

- file name

- file hash

- parent process (browser? explorer?)

- Mark-of-the-Web (MOTW) if available

2) Installer chain spawns unusual child activity

Instead of a clean, predictable installer tree, we see:

- installer process launching a child that leads to

rundll32.exe

This is one of those moments where you stop treating it like “software installation” and start treating it like “execution chain”.

Why rundll32 matters:

Loaders frequently use rundll32.exe as an execution proxy because it blends into Windows noise and can run exported DLL functions cleanly.

3) Persistence appears quickly

A scheduled task is created within minutes of the suspicious execution chain.

This is a common loader behavior:

- establish persistence quickly

- phone home

- wait for stage 2

Why scheduled tasks matter:

They are reliable, flexible, and often ignored until too late.

4) Outbound beaconing begins

Soon after persistence:

- regular outbound HTTPS sessions to a domain the environment hasn’t seen before

- consistent cadence (not “human browsing” patterns)

This is where containment decisions are made. You don’t wait for “ransomware” to appear. The loader stage is when you can still cut the chain cheaply.

The turning point: what made it “obviously malicious”

In many environments, a fake update chain can be argued away as “weird installer behavior” until one detail appears that collapses the debate:

A DLL executed via rundll32 from a user-writable directory

That combination is the tell:

rundll32.exe+ user-writable path + proximity to a fresh download + new task + new outbound domain

Even if you never fully reverse the payload, you can make a defensible assessment:

This is consistent with a loader chain delivered via social engineering, likely intended to establish persistence and fetch additional payloads.

And that is enough to act.

What this “loader stage” usually means

Fake browser update lures are used for one reason: scale.

The first-stage payload is typically not the end goal. It’s the entry point.

Common follow-ons include:

- information stealers (credentials, cookies, tokens)

- remote access tooling

- additional loaders (multi-stage)

- access brokerage leading to ransomware later

The loader is the “front door wedge”. If you kill it early, you often prevent the expensive part of the incident.

How I’d investigate this (the practical flow)

Here’s the flow I use when the pattern looks like “fake update → loader”:

Step 1: Confirm the delivery vector

- Was the parent process a browser?

- Is there a referrer URL or download source in browser history?

- Is MOTW present? (If yes, treat as internet-delivered)

Step 2: Build the process story

- Parent → child chain

- Command lines (especially rundll32)

- File write events around execution time

Step 3: Pull persistence artifacts immediately

- Scheduled task name, trigger, action

- Export task XML if possible

- Check common persistence neighborhoods (Run keys, services, startup)

Step 4: Pivot to network

- Domain first-seen in your environment

- URI patterns (repeatable endpoints)

- Beacon interval (regularity is a signal)

Step 5: Scope fast

- Search for the same scheduled task name pattern across endpoints

- Search for the same rundll32 command-line pattern

- Search for the same outbound domain/URI pattern

Containment strategy: what I’d do before reverse engineering anything

This is where a lot of teams lose time. They want perfect answers before acting.

You don’t need perfect answers to cut a loader chain.

Practical actions: 1) Isolate the host (or restrict egress if isolation is heavy-handed) 2) Preserve volatile artifacts (process tree, network connections, task XML) 3) Reset credentials for the user (especially if browser artifacts were accessed) 4) Block the domain/URI pattern (through change control) 5) Hunt for the persistence + execution signature across the fleet

Reverse engineering can come later. The business risk doesn’t wait.

“Could this be benign?” (the only honest way to frame it)

There are always edge cases:

- some legitimate software uses odd chains

- some enterprise tooling triggers weird DLL execution

But tradecraft is about probabilities anchored in evidence.

This combination is rarely benign in real environments:

- newly downloaded “update” file

- suspicious installer tree

rundll32executing DLL from user-writable path- new scheduled task shortly after

- beaconing to new infrastructure

If you see that pattern, you treat it as hostile until disproven.

Mini exercise: test your own environment

If you run a lab or even just a test workstation:

- Create a benign scheduled task

- Execute a benign DLL export via rundll32 (in a controlled lab)

- Watch what telemetry you actually capture (EDR/Sysmon/Windows logs)

The goal isn’t to learn exploitation. It’s to validate whether your detection stack can even see the shape of this activity.

Most teams assume they can. Many can’t.

Artifact Annex (field notes)

Host artifacts to collect

- Downloaded file

- name, hash, size, path

- MOTW / Zone.Identifier (if present)

- Execution chain

- parent process (browser vs explorer)

- installer command line

- rundll32 command line (critical)

- Dropped payload

- DLL path, timestamps, hash

- Persistence

- scheduled task name

- triggers

- action path/arguments

- task XML export

Network artifacts to collect

- destination domain + resolved IPs

- first-seen timestamp in environment

- URI patterns (repeatable endpoints)

- beacon interval and regularity

- TLS certificate metadata (if available)

Detection ideas (practical, high-signal)

- Alert on rundll32 executing a DLL from:

C:\Users\*\Downloads\C:\Users\*\AppData\Local\Temp\C:\Users\*\AppData\Roaming\

- Correlate within a short window (e.g., 10 minutes):

- new download execution + rundll32 + scheduled task creation

- Hunt for:

- scheduled tasks created by non-admin user contexts

- tasks whose action points to user-writable paths

- Network detection:

- new domain + consistent periodic HTTPS sessions

- unusual user-agent strings (stale browser versions, generic libs)

Closing thought

Fake browser updates succeed because they blend into normal behavior.

You can’t “train” this away completely. What you can do is detect the transition point where normal browsing becomes loader execution — and that transition leaves artifacts.

If you can catch:

- the rundll32 execution pattern,

- the rapid scheduled-task persistence,

- and the new beaconing infrastructure,

…you can often stop the intrusion before it becomes an incident worth naming.