Lumma vs Commodity Stealers: The Artifact Differences

Stealers often look identical at first glance: browser DB access, cookie theft, rapid exfil, and a flood of IOCs. But there are consistent artifact-level differences that let you classify the intrusion fast—even without perfect family attribution. This post compares Lumma-style tradecraft against common commodity stealers and shows the practical pivots that separate them in real telemetry.

Why this comparison matters

When a stealer case lands, everyone wants the same thing:

“What is it?”

But if you work incidents long enough, you learn a more useful question:

“What does it behave like, and what do I do next?”

Stealers are a volume game. Many families reuse the same tactics:

- staged loaders

- user execution (fake updates, cracks, attachments)

- browser credential store access

- cookie and token theft

- rapid exfiltration

So if your process is “wait for perfect attribution,” you lose time. If your process is “classify by artifact behavior and respond,” you win time.

This post is not “reverse engineering Lumma.” This is Family vs Family through a responder’s lens: the artifact differences that help you triage, scope, and act.

The baseline: what all stealers tend to do

Before we compare, anchor the common ground. Most stealers will show some combination of:

Host artifacts

- access to Chrome/Edge profile data:

Login Data,Cookies,Local State

- access to Firefox stores:

logins.json,cookies.sqlite,key4.db

- short-lived staging in:

AppData\Local\TempAppData\Roaming

- archive creation (zip/rar/7z) or staging directories

- persistence (sometimes) but often not, depending on delivery model

Network artifacts

- outbound HTTPS to new or low-reputation infrastructure

- short burst exfil rather than long interactive C2

- beacon-like check-ins are possible, but many stealers are “fire and forget”

This baseline is why triage can feel repetitive. But the differences are there—if you look in the right places.

Think in “stealer archetypes”

In practice, I treat stealer families as falling into archetypes.

Archetype A: “Access broker” style

- more likely to include persistence or re-entry logic

- may stage secondary payloads

- infrastructure may be reused or structured in a more “operation” style

Archetype B: “Smash-and-grab” commodity

- fast execution

- grab browser/crypto/Discord/Telegram data

- exfil quickly

- minimal persistence

Lumma-style campaigns are often closer to A than many generic commodity stealers.

You can see that in artifacts.

The comparison: where Lumma-style cases often differ

Important: this is about patterns, not absolutes. Threats evolve and overlap.

1) Delivery and initial execution: more consistent “campaign shape”

Commodity stealers often arrive via:

- cracks, keygens, YouTube “how to”

- random attachments

- generic fake installers

Lumma-style campaigns frequently show:

- strong social engineering packaging (fake update flows, fake document viewers, fake CAPTCHA steps)

- consistent landing page behavior across victims

- repeatable staging chains that look “templated”

Artifact clue:

When multiple incidents share the same landing-page UX and similar staged execution chain, you’re seeing campaign discipline rather than random commodity spray.

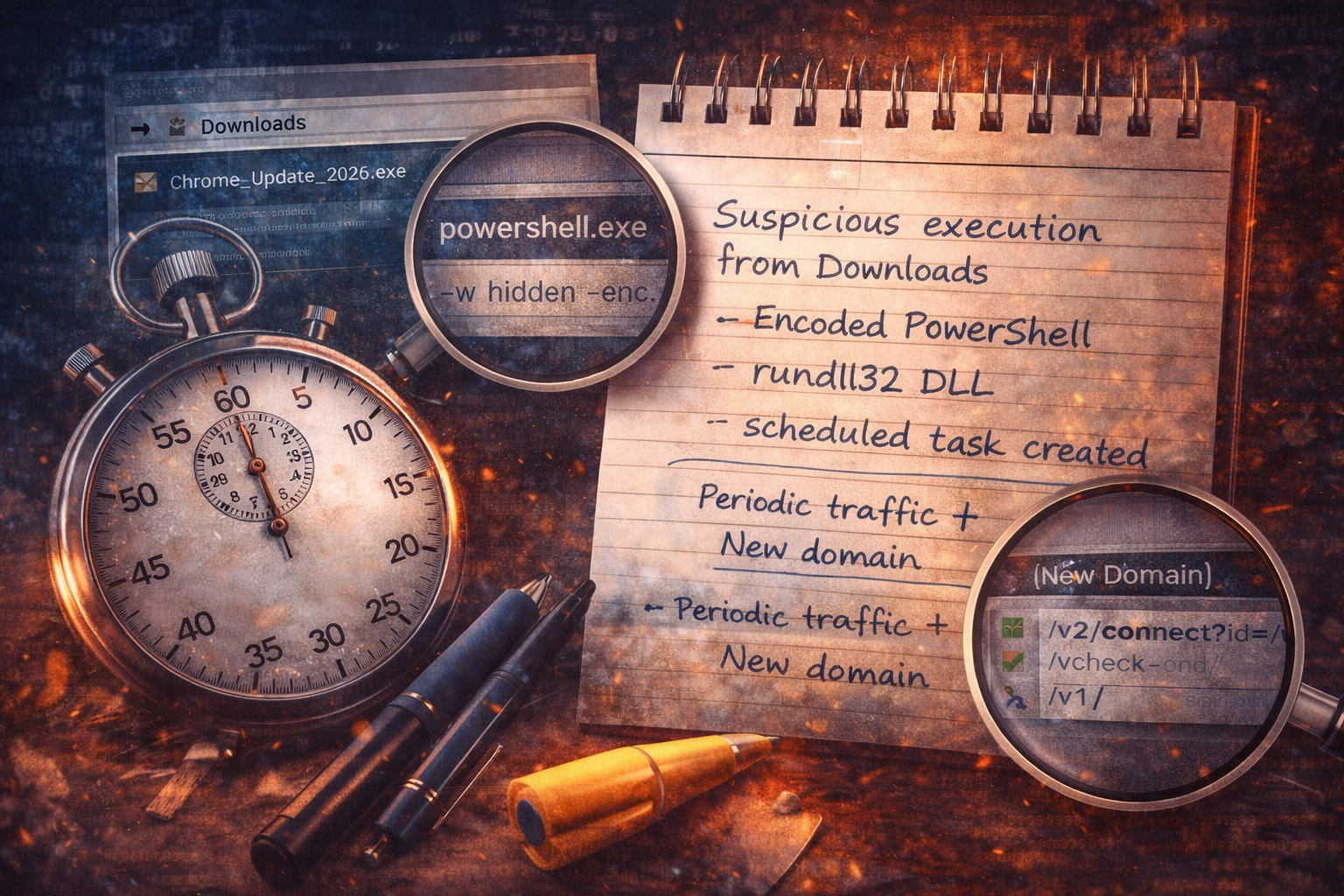

2) Staging and execution chain: the “hinge” artifacts

Commodity stealers often:

- execute directly as an EXE

- drop into Temp/Roaming

- run and exfil quickly

Lumma-style cases often show more:

- loader usage or DLL execution via LOLBins

- “proxy” execution (rundll32, PowerShell staging) that looks like an operational preference

High-signal hinge chain examples:

- fake update EXE → PowerShell (hidden/encoded) → dropped DLL → rundll32 export execution

- quick persistence creation to guarantee re-run on logon

You do not need to name the family to recognise the posture.

3) Persistence: not always present, but when it is, it is telling

Many commodity stealers are one-shot:

- execute

- steal

- exfil

- done

If you see persistence, it shifts your risk posture.

Lumma-style operations may be more likely to:

- establish persistence via scheduled task

- maintain a foothold long enough for re-entry or follow-on payload decisions

Artifact clue:

A scheduled task that points to user-writable payload paths, created shortly after initial execution, is more consistent with a “keep access” posture than a smash-and-grab.

4) Exfil behavior: burst vs structured

Commodity stealers often:

- compress data locally

- perform a quick outbound upload

- end execution

Lumma-style cases can look similar, but you may also see:

- more structured “check-in” logic prior to collection

- a consistent check-in endpoint pattern across victims

- operationally repeated URI shapes and cadence

Network clue:

If the host begins with periodic check-ins, then performs browser store access and rapid upload, that suggests collection is gated on a successful server response (i.e., a controlled workflow).

5) Post-compromise: what happens after matters most

This is the real differentiator.

Commodity stealers often lead to:

- account takeover attempts

- credential stuffing

- opportunistic abuse

Lumma-style operations are frequently associated with:

- access brokerage behavior

- resale and follow-on intrusion risks

- a higher likelihood that stolen sessions will be operationalized quickly

Operational clue:

If you see rapid reuse of stolen sessions (cloud app access, mailbox rule creation, OAuth consent abuse), treat it as an access-broker style problem—whether or not you stamp “Lumma” on it.

The responder’s classification method (fast and useful)

When the case lands, I classify based on:

A) Evidence of staging discipline

- repeatable chain

- consistent lure

- consistent infrastructure patterns

B) Evidence of foothold intent

- persistence

- re-entry logic

- staged execution rather than direct run

C) Evidence of operationalized access

- token/session reuse

- mailbox rules

- OAuth app grants

- privileged account exposure

If A+B+C are present, you are not dealing with “generic commodity noise.” You are dealing with a more serious intrusion workflow.

Practical hunt pivots: the artifact differences you can actually search

Host pivots

- non-browser processes accessing:

Login Data,Cookies,Local State

- archive creation from browser profile directories

- DLL execution via rundll32 from AppData

- scheduled tasks created within minutes of suspicious execution

- PowerShell hidden/encoded in the execution chain

Network pivots

- first-seen domains contacted shortly after download execution

- stable URI shapes across victims (

/connect,/check,/v2/) - periodic check-ins followed by a larger outbound transfer burst

- recurring infrastructure patterns (same ASN ranges, similar domain naming)

Response posture: what changes when it smells like “Lumma-style” vs commodity

You do not respond to all stealers the same way. Here is what shifts:

If it looks like commodity smash-and-grab

- isolate host (depending on org policy)

- reset user credentials

- revoke sessions/tokens

- block IOCs

- close with a standard scope check

If it looks like access-broker / disciplined operation

- assume session reuse and follow-on intrusion risk

- prioritize:

- session revocation at scale

- OAuth consent review

- mailbox rule auditing

- privileged access review

- widen the hunt window

- treat it as an intrusion entry event, not a one-off stealer pop

This is where many teams under-react: they do password resets but leave sessions active, or they do endpoint cleanup but ignore cloud identity abuse.

Common mistakes in stealer cases

- Spending hours debating family attribution while sessions remain active

- Resetting passwords but not revoking tokens/sessions

- Blocking domains without scoping persistence artifacts

- Treating it as “one host” when the same lure is likely hitting others

The fastest wins are procedural, not technical.

Artifact Annex (field notes)

Key browser artifacts

Chromium

...\User Data\Default\Login Data...\User Data\Default\Cookies...\User Data\Local State

Firefox

...\Profiles\<profile>\logins.json...\Profiles\<profile>\cookies.sqlite...\Profiles\<profile>\key4.db

High-signal “family vs family” indicators

- loader-style execution chain (PowerShell → DLL → rundll32)

- scheduled task persistence pointing to user-writable payload

- check-in cadence before collection and upload

- repeated URI shape across multiple victims

Response pivots

- revoke sessions and refresh tokens

- audit OAuth grants and mailbox rules

- scope for identical task names, DLL paths, and URI patterns

Closing thought

Family names matter for reporting. They do not matter as much for response.

If you can classify a stealer incident by artifact behavior, you can:

- contain faster

- scope better

- reduce impact

Call it Lumma, call it commodity, call it “stealer-style intrusion.”

The artifacts will still tell you what to do next.