Mispadu Banking Trojan — Latin America’s Credential Harvester

Mispadu is a Latin American–focused banking trojan that blends phishing, malvertising, and social engineering with a modular stealer and remote control back-end. This deep dive walks through how it spreads, how it operates, and how defenders can detect and contain it.

Mispadu is a Latin American–centric banking trojan and stealer that primarily targets users in Brazil, Mexico, Chile and surrounding regions. It focuses on credential theft for online banking, payment portals, and local services, and it’s typically delivered via:

- Malspam with fake invoices, tax documents, or courier notifications.

- Malvertising and SEO poisoning that serve trojanised installers for common tools.

- Aggressive social engineering, often in Portuguese or Spanish, to trick users into entering credentials directly into fake overlays.

Once executed, Mispadu:

- Deploys a multi-stage loader chain, often using MSI, script droppers, and unusual file formats.

- Uses Windows persistence (shortcuts, scheduled tasks, registry entries) to survive reboots.

- Hooks browsers and injects phishing overlays on top of legitimate banking websites.

- Exfiltrates credentials, tokens, and sensitive data to attacker-controlled C2 servers.

- Provides remote access features that let operators perform fraudulent transactions in real time.

This post breaks down Mispadu’s delivery, internal behaviour, forensic artefacts, and defensive strategies, with a focus on how to hunt it in real environments rather than just memorising IOCs.

1. Threat Landscape: Where Mispadu Fits

Mispadu is one of several Latin American banking trojans that share tradecraft and tooling patterns, alongside families like Grandoreiro, Guildma, and Mekotio.

All of them:

- Target regional banks and services (e.g., Brazilian and Mexican financial portals).

- Rely heavily on local-language lures and culturally familiar pretexts.

- Use a loader + overlay architecture: first gain execution, then present fake banking screens on top of real ones.

Where Mispadu distinguishes itself is in its:

- Extensive use of custom packers, script chains, and geofencing to avoid analysis outside LATAM.

- Focus on session hijacking and overlays rather than just static credential theft.

- Flexible C2 protocol and configuration, which make simple static signatures fragile over time.

For defenders outside Latin America, Mispadu may look like “just another trojan”. For organisations with regional operations or customers, it’s absolutely relevant — especially if you provide banking-as-a-service, payment platforms, or financial SaaS used by LATAM audiences.

2. Initial Access: How Victims Get Mispadu

Mispadu’s operators continuously experiment with delivery methods, but there are three recurring patterns you’ll see in telemetry.

2.1 Malspam with realistic local lures

The most common vector is still phishing emails, typically written in Portuguese or Spanish and themed around:

- Invoices and overdue bills (boleto bancário, electricity, phone, internet).

- Tax-related notifications (fake revenue service / Receita Federal messages).

- Delivery / courier notices (Correios, DHL, regional couriers).

The emails often contain:

- A link to a malicious hosting site; or

- A compressed attachment (

.zip,.rar,.7z) containing a shortcut, script, or installer.

The lure usually claims that clicking the link or running the file is needed to:

- View a bill or proof of payment.

- Download an updated tax form.

- Confirm a delivery or reschedule a package.

2.2 Malvertising and trojanised installers

Mispadu crews have also abused malvertising and SEO poisoning. The pattern is familiar:

- A user searches for a popular tool (e.g., PDF editor, video converter, “boleto viewer”, invoice generator).

- A sponsored result or poisoned SEO result points to a website that looks legitimate.

- The site serves an installer or compressed file which actually contains a Mispadu loader.

These installers often masquerade as legitimate software:

- “Comprovante_Visualizador_Setup.exe”

- “Atualizador_Fiscal_2024.msi”

- “PDF_Invoice_Tool_Portable.zip”

From the user’s perspective, they simply downloaded a “helper” tool that many peers also use. From the attacker’s perspective, they’ve targeted users who self-identify as likely to handle payments and invoices.

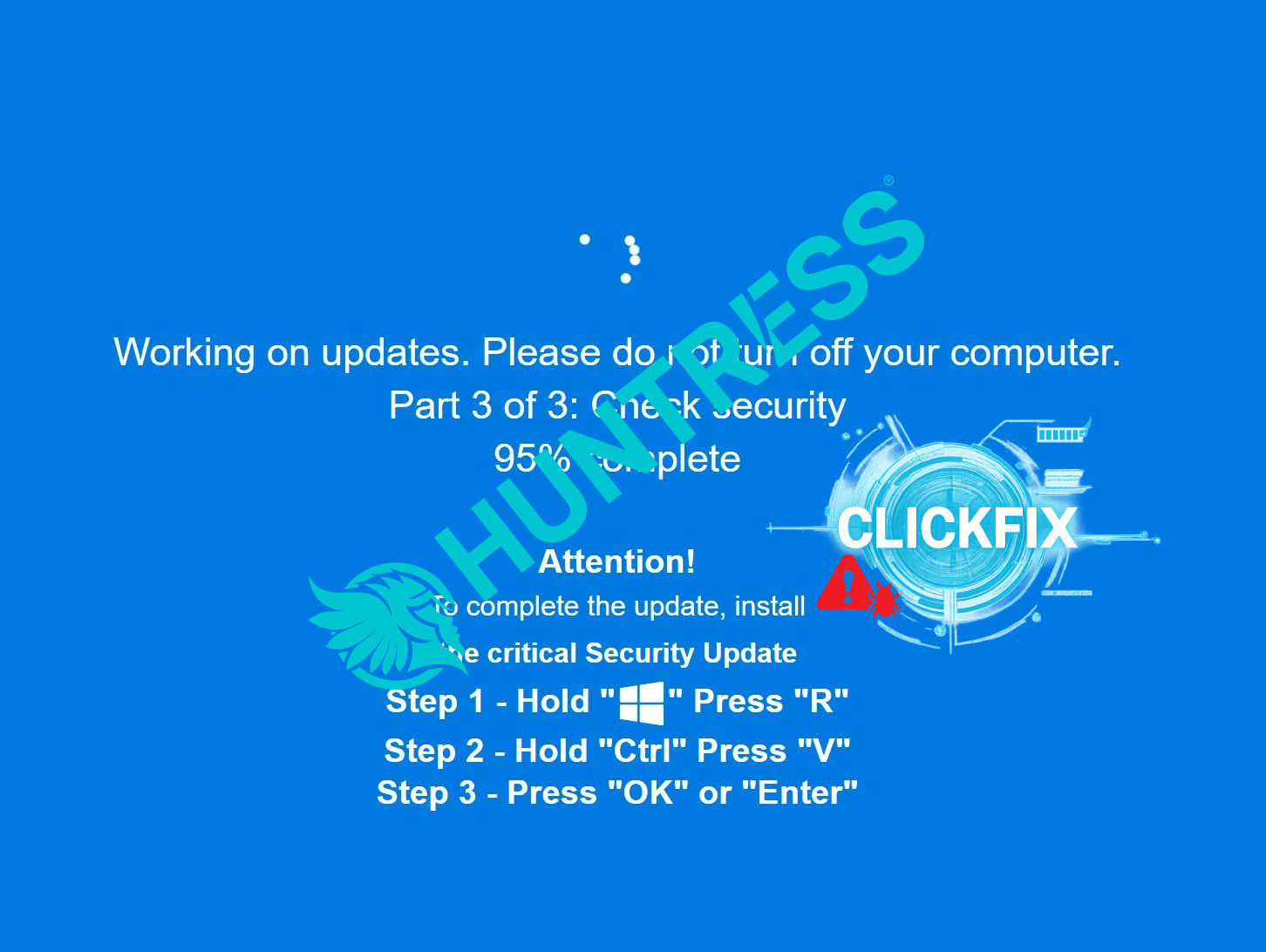

2.3 Social engineering and fake update flows

Some campaigns present fake browser update prompts or app-update flows. A user is told, in Portuguese or Spanish, that they must:

- Update their browser or Flash-like plugin to view a secure document, or

- Install an “encryption component” to access a banking or government portal.

These flows may be chained to:

- A ZIP archive with a script (.BAT, .VBS, .JS) loader.

- A signed but malicious MSI that wraps the downloader logic.

- Obfuscated PowerShell or AutoIt execution.

Across all these vectors, the core idea is simple: turn routine financial admin tasks into malware execution events.

3. The Mispadu Infection Chain

While individual campaigns vary, most Mispadu infections follow a multi-stage chain. Understanding the stages helps when reconstructing incidents from logs and artefacts.

3.1 Stage 0 — User interaction

- User opens a phishing email or visits a malicious site.

- User clicks a link or attachment claiming to be a document or tool.

- The browser downloads an archive or installer to the Downloads folder.

Forensically, you’ll see entries in:

- Browser history (HTTP GET to the hosting domain).

- Download manager logs (if the browser tracks them).

- Email client logs (message ID, from/to, URL, attachment name).

3.2 Stage 1 — Loader execution (scripts, shortcuts, MSIs)

The first executable stage is usually not the core trojan. Instead, you see:

- A LNK shortcut that actually runs PowerShell or a script interpreter.

- A script file (

.vbs,.js,.bat) that downloads another component. - A MSI that installs what looks like a benign app while deploying the loader in the background.

Key behaviours include:

- Dropping files into

%TEMP%,%APPDATA%,%LOCALAPPDATA%, orC:\Users\Public. - Using

curl,bitsadmin, or PowerShellInvoke-WebRequestto pull down payloads. - Adding registry Run keys or scheduled tasks for persistence.

From a DFIR perspective, this is where process ancestry matters:

winword.exe/outlook.exe→wscript.exe→ unknown script.- Browser (

chrome.exe,msedge.exe) →msiexec.exe→ unsigned MSI.

3.3 Stage 2 — Main Mispadu payload

The main Mispadu component is typically a Windows executable encoded or packed in one or more layers. Common traits include:

- Use of custom packing / encryption to evade static detection.

- Embedded configuration with C2 domains, campaign IDs, banking targets, and language settings.

- Initial environment checks (OS version, locale, virtualisation hints) to avoid sandboxes.

When it runs, Mispadu:

- Establishes persistence.

- Connects to its C2 to register the victim and fetch updated config.

- Starts monitoring browser activity and system state for banking/targeted sites.

3.4 Stage 3 — Overlay and credential capture

The signature feature of Mispadu and similar trojans is the use of browser overlays:

- The malware tracks active window titles and URLs.

- When a user navigates to a targeted banking or payment domain, it triggers.

- It displays a fake login or MFA window that looks almost identical to the real one.

- Credentials entered in the overlay go straight to the attacker, even if the back-end site never receives them.

Sometimes the overlay will:

- Ask for extra information (full card details, CPF/SSN-like identifiers, security questions).

- Provide error messages that nudge the user into retrying or sharing more details.

In parallel, the trojan may capture:

- Keystrokes, clipboard contents, and screenshots.

- Browser cookies and session tokens, allowing the operator to hijack an existing authenticated session.

3.5 Stage 4 — Fraud and post-compromise activity

Once the operator has credentials and/or session tokens, they may:

- Log into banking portals from their own infrastructure.

- Initiate transfers, add new beneficiaries, or change contact details.

- Use remote access capabilities of Mispadu to operate from the victim’s machine, reducing fraud-detection signals.

In some campaigns, Mispadu can also:

- Download additional modules (e.g., more aggressive stealer, remote shell).

- Update its configuration or binaries to adapt to banking site changes.

4. Capabilities in Detail

4.1 Data theft and credential harvesting

Mispadu focuses on:

- Banking credentials (username, password, PIN, token/MFA codes).

- Payment card data when portals request card verification.

- Local e-commerce and government portal logins.

-

Stored browser credentials from:

- Chromium-based browsers (Chrome, Edge, Brave, Opera).

- Firefox-based browsers.

It may use OS APIs or browser-specific paths to extract saved passwords and cookies, then exfiltrate them over encrypted channels.

4.2 Remote control and automation

While not as full-featured as some RATs, Mispadu commonly supports:

- Command execution — run arbitrary commands or scripts.

- Screenshot capture — watch what the user is doing.

- File operations — upload/download files, modify host artefacts.

- Browser manipulation — open URLs, focus windows, trigger overlays.

This lets operators orchestrate fraud in a semi-automated way: they can prompt the user to “confirm a transaction”, “update a token”, or “fix an error” using crafted screens.

4.3 Evasion and anti-analysis

To avoid detection and analysis, Mispadu campaigns frequently implement:

- Geofencing — only deliver payloads if IP/locale match targeted countries.

- Environment checks — basic VM/sandbox artefact detection, aborting execution if triggered.

- Code obfuscation — encrypted strings, junk code, indirect API calls.

- Delayed execution — waiting several minutes after initial run before contacting C2.

Some campaigns deliberately abuse legitimate tools (AutoIt, signed installers) to blend in with admin activity.

5. Forensic Artefacts: What to Look For

When investigating a suspected Mispadu infection, think across several layers: email/web, endpoint, and network.

5.1 Email and web artefacts

- Original phishing emails (subject, sender, reply-to, URLs, language).

- Attachments: names, hashes, and internal structure (is it script-laden ZIP/MSI?).

-

Browser history entries that match:

- Malvertising landing pages.

- Malicious file-hosting services.

- Fake “viewer” / “update” pages.

- Download logs (browser-level or OS-level) showing when the user retrieved the payload.

These artefacts help you identify who else received similar lures and whether the campaign is broader than one victim.

5.2 Endpoint artefacts

On the host itself, focus on:

- Prefetch files for unusual executables (Mispadu payloads and loaders).

-

Files dropped in user-writable locations:

%APPDATA%\Roaming\<random>\%LOCALAPPDATA%\Temp\C:\Users\Public\

-

Registry persistence:

HKCU\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Runentries pointing to suspicious binaries or scripts.- Scheduled tasks in

C:\Windows\System32\Tasksreferencing user profile paths.

-

Shortcut modification:

- Browser or banking app shortcuts modified to launch via an intermediate script/executable.

- Log files the malware may use to store configuration or captured data prior to exfil.

Timeline analysis of these artefacts (creation and modification times) helps reconstruct when infection occurred and how long it has been active.

5.3 Process and memory

EDR/Sysmon style telemetry is invaluable:

- Parent-child relationships (Office → script engine → unknown EXE).

- Processes running from

Downloads,%TEMP%, or uncommon folders. -

Long-lived processes that:

- Inject into browsers.

- Create global hooks.

- Periodically connect to external IPs/domains.

If you can capture memory:

- Look for injected code in browser processes.

- Extract strings and configuration (C2 URLs, targeted banks, mutex names).

- Identify overlay HTML/JS content embedded in the payload.

5.4 Network indicators

Network patterns vary, but common traits include:

- Outbound HTTPS to low-reputation or freshly registered domains.

- Hostnames that may mimic legitimate services but are slightly off.

- Periodic beacons with small payloads, followed by larger bursts when overlays are triggered or data is exfiltrated.

Correlate:

- First seen connection times.

- Users and hosts making those connections.

- Whether connections spike during local business hours, when banking activity is highest.

6. Detection and Hunting Ideas

6.1 Behavioural detection on endpoints

Static signatures are brittle due to packing/obfuscation, so emphasise behaviour:

- Alerts when Office or PDF readers spawn scripting engines and installers.

-

Detection for unsigned executables running from user profiles that subsequently:

- Create Run keys or scheduled tasks.

- Spawn browser processes or inject into them.

- Open network connections to untrusted destinations.

-

Rules for suspicious PowerShell:

- Encoded commands.

Invoke-WebRequestorStart-BitsTransferdownloading executable content.- Process trees where

powershell.exeis a child of email or browser processes.

6.2 User-based and application-based signals

Because Mispadu uses overlays and social engineering:

- Watch for multiple failed logins to banking portals from the same host.

- Monitor if users report weird extra prompts in banking or payment apps.

- If you control banking front-ends, check for anomalous device fingerprints or IPs that start transactions shortly after a legitimate user session, potentially with mismatched geolocation.

6.3 Network and proxy-level controls

Implement controls such as:

- SSL inspection (where legally and ethically permissible) to identify unusual destinations.

- Block lists for known C2 domains and malware-hosting sites.

- Egress filtering so that endpoints cannot directly talk to the entire internet, only required ranges.

For hunting:

- Search historical proxy/DNS logs for known Mispadu indicators if you have them.

- Look for machines that, prior to fraud reports, contacted multiple uncommon Brazilian/Mexican-hosted domains linked to malvertising.

7. Response and Containment Strategy

When you confirm or strongly suspect Mispadu on an endpoint, treat it as high-impact due to the financial risk.

7.1 Immediate containment

- Isolate the endpoint from the network.

- Notify internal fraud / payments teams if customer or internal banking logins might be affected.

- If the machine is used for privileged banking operations (e.g., corporate treasury), escalate immediately.

7.2 Credential hygiene

Assume that any credentials entered on the system after infection are compromised:

- Reset online banking and financial portal credentials.

- Reset email credentials used to receive MFA codes or banking notifications.

- Rotate passwords for any corporate portals accessed from the machine.

- If browser password stores are used, reset those credentials as well.

7.3 Host triage

On the affected host:

- Acquire volatile data (if possible) before powering down.

- Capture a disk image if the case warrants deep investigation or legal action.

-

Collect:

- Prefetch, Amcache, Shimcache artefacts.

- Registry hives for Run keys and recent file execution.

- Browser history and downloads.

- Relevant log sets (EDR, Sysmon, Windows event logs).

Use these to build a detailed infection timeline and verify whether:

- Other malware families were also present.

- The operator used the host for remote access beyond banking sites.

7.4 Environment-wide scoping

Search for:

- Similar artefacts (same binaries, registry keys, scheduled tasks) on other endpoints.

- Email logs showing who else received the same phishing messages.

- Proxy/DNS logs for other machines talking to the same infrastructure.

Even if Mispadu seems “single-user focused”, treat any evidence of lateral movement or multi-host infections as a potential wider intrusion.

8. Preventive Controls and Awareness

To reduce the likelihood and impact of Mispadu and similar trojans:

-

Awareness training tailored to LATAM users:

- Examples of real local-language lures.

- Demonstrations of overlay attacks vs real banking pages.

- Emphasis on verifying URLs and using bookmarked banking links.

-

Endpoint hardening:

- Application control policies (block execution from

DownloadsandTemp). - Restrict or monitor script engines (PowerShell, wscript, cscript).

- Enforce up-to-date browsers and OS patches.

- Application control policies (block execution from

-

Banking hygiene:

- Use dedicated, hardened workstations for corporate banking activities.

- Avoid installing unrelated tools or browsing general internet from those machines.

- Where possible, use hardware tokens or mobile app MFA that is harder to man-in-the-browser.

-

Financial controls:

- Dual-approval for high-value transfers.

- Limits and anomaly detection on new beneficiaries and large transactions.

- Strong out-of-band confirmation for changes to contact details and payment instructions.

9. Closing Thoughts

Mispadu is a reminder that regional threats can be just as sophisticated and dangerous as globally known malware families. For organisations with exposure to Latin American customers, partners, or operations, it’s not a niche curiosity — it’s a core fraud and cyber risk.

You don’t need to recognise every string in every sample. What matters is understanding the patterns:

- Phishing and malvertising chains that end in “viewer” tools or “updates”.

- Multi-stage script and installer loaders depositing trojans into user-space directories.

- Browser overlays and man-in-the-browser behaviour that subvert legitimate financial workflows.

By focusing on those behaviours, tuning your logging and detections, and building repeatable playbooks, you can turn Mispadu from a lurking, opaque threat into a well-understood risk you can monitor, hunt, and contain.

Ultimately, this is the same playbook you’ll reuse for other regional banking trojans — just with different names, overlays, and C2 infrastructure. Learn Mispadu well, and you’ll be better positioned for whatever its successors look like.