Scheduled Tasks: The Persistence Mechanism That Never Dies

If I had to bet on one persistence mechanism showing up again and again in real incidents, it’s scheduled tasks. They’re reliable, flexible, easy to camouflage, and often under-monitored. This post breaks down how attacker tasks tend to look, what defenders should log, and the fastest way to hunt suspicious tasks at scale.

The artifact that keeps showing up

When incidents get messy, the same question comes up:

“How does it keep coming back?”

Nine times out of ten, persistence isn’t sophisticated. It’s just reliable.

And scheduled tasks are reliability in weapon form.

They survive reboots. They can run as the user, SYSTEM, or service accounts. They can trigger on logon, idle, time, network, workstation unlock—almost anything. They’re built into Windows, so they blend in by default.

If a loader’s job is “stay alive and call home,” tasks are the easiest way to do it.

The “two tasks” problem: normal vs malicious

Here’s why tasks are so effective: Windows already has a lot of them.

So defenders get numb to them.

Attackers exploit that by naming tasks like:

UpdateCheckChromeUpdateTaskWindowsUpdateServiceSecurityHealthMonitor- anything that looks like it belongs under

\Microsoft\Windows\...

The goal is not perfect stealth. It’s not standing out at a glance.

What attacker tasks usually do (the practical categories)

Most malicious scheduled tasks fall into one of these patterns:

1) Re-run the loader on logon

- Trigger: At logon

- Action: launch a DLL via rundll32, or execute a dropped EXE

Why: guarantees execution whenever the user returns.

2) Beacon on a timer

- Trigger: Every 1/5/10/60 minutes

- Action: run a script, a LOLBin, or a hidden binary

Why: creates predictable C2 behavior and quick recovery.

3) “Delayed execution” for evasion

- Trigger: At startup + delay

- Action: run after 2–10 minutes

Why: dodges some short-lived detonation/sandbox timing and reduces correlation.

4) “System-looking” monitoring tasks

- Trigger: On idle / workstation unlock / network available

- Action: looks like telemetry, but it’s persistence

Why: it blends into normal operations patterns.

The tell: tasks that execute from user-writable paths

You can name a task anything. But the action path tells the truth.

A high-signal suspicious pattern is:

- task action points to Downloads, AppData, Temp, Roaming, or a weird new directory in the user profile

Legitimate vendor updaters typically install to:

Program Files- vendor directories with stable naming

- signed binaries with consistent provenance

Malicious tasks often point to:

- user-writable locations that don’t require admin rights

- filenames designed to look “system-y”

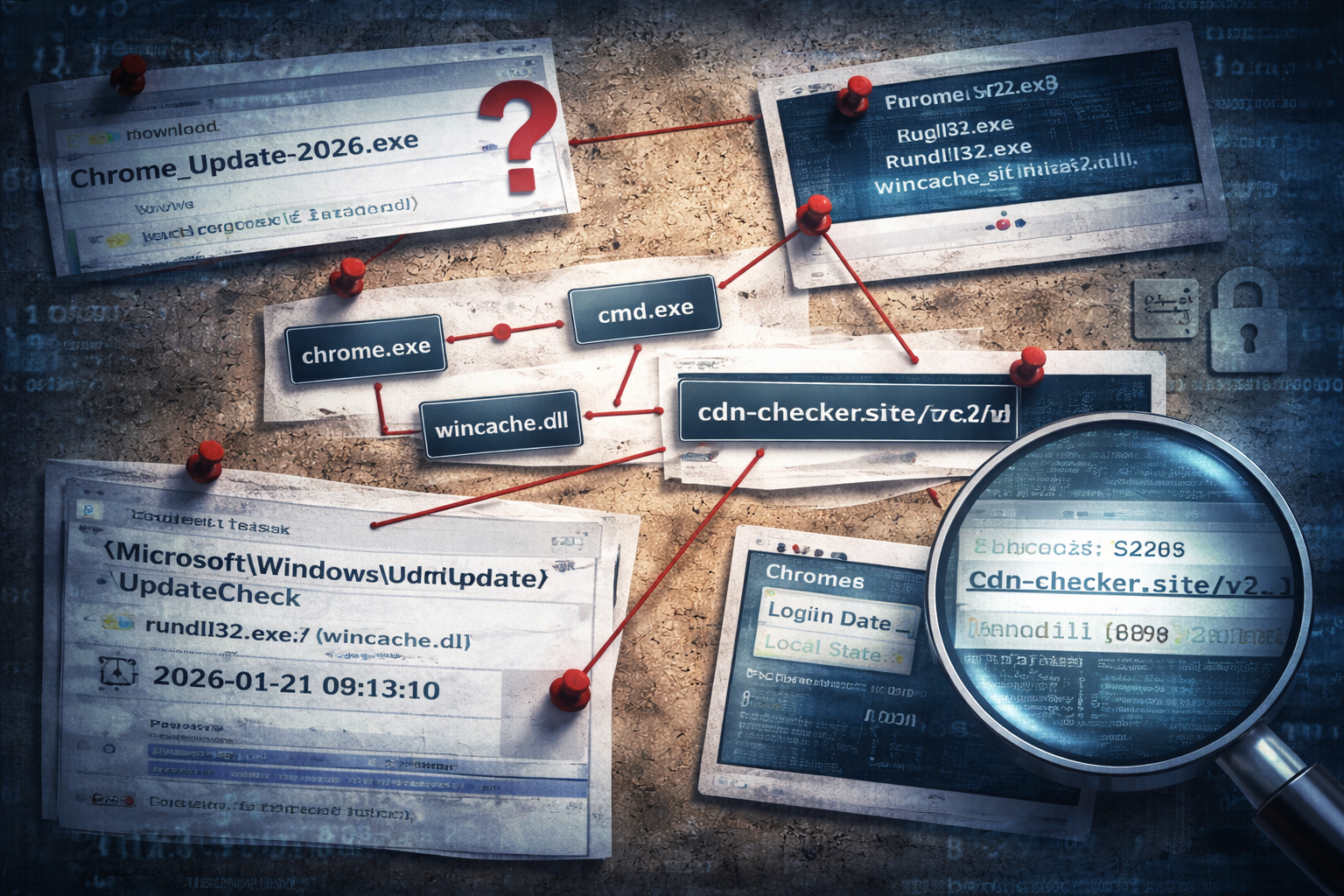

A micro casefile: “UpdateCheck” that wasn’t Windows Update

This is a pattern that shows up constantly in loader cases.

- Task name:

\Microsoft\Windows\Update\UpdateCheck - Trigger: At logon

- Action:

rundll32.exe "<user>\AppData\Roaming\WinCache\wincache.dll",Start

Everything about the name and folder tries to look legitimate.

But the action reveals:

rundll32used as a proxy execution mechanism- DLL is stored in a user profile folder

- an export name like

Start(common and generic)

You don’t need to debate it. You isolate and scope.

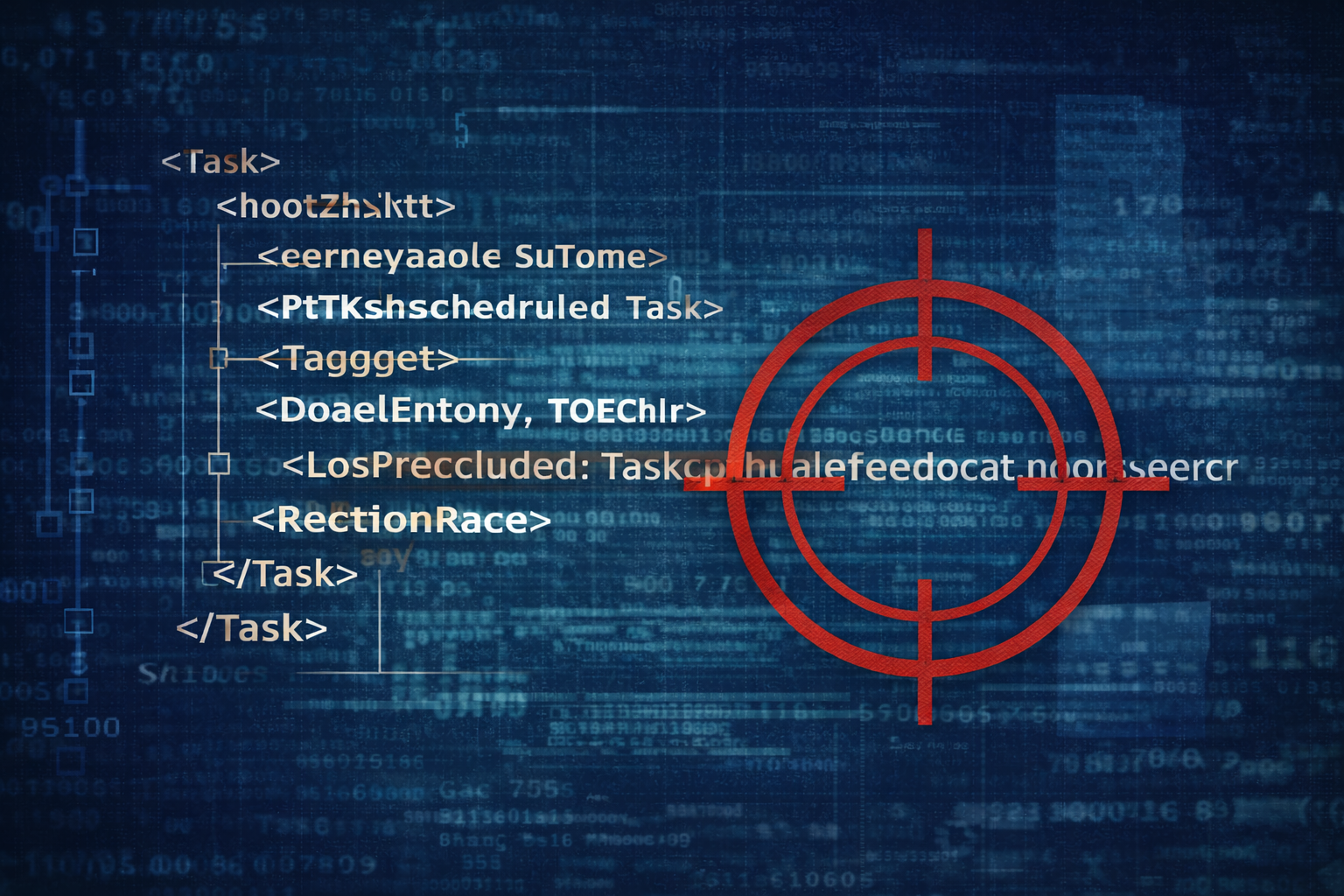

What you should log (because without logs, tasks are invisible)

If you only take one thing from this post:

Task creation and modification events must be visible.

At minimum, you want:

- task creation time

- task name + folder path

- author / user context

- triggers

- action command + arguments

- the task XML (best source of truth)

Even if you’re not doing full DFIR, this single artifact class is worth instrumenting.

Hunting scheduled tasks without drowning

The shortlist: what I look for first

If I’m scoping fast, I prioritize tasks with:

1) Recent creation time (new persistence is loud) 2) User-writable action paths 3) LOLBin actions (PowerShell, cmd, mshta, rundll32, regsvr32) 4) Suspicious arguments (encoded PowerShell, hidden windows, odd DLL exports) 5) Camouflage naming (looks like Windows update/security tooling)

These five checks catch a large percentage of attacker tasks in real incidents.

Common camouflage tricks (so you don’t get fooled)

Attackers often:

- place tasks under

\Microsoft\Windows\...folders - use “Update”, “Health”, “Telemetry”, “Security” in names

- pick triggers that mimic system maintenance

- use signed Windows binaries (LOLBin execution) to run unsigned payloads

None of these are proof alone.

But combined with user-writable payloads and recent creation time, it becomes hard to argue benign.

How to respond when you find a suspicious task

Don’t do this first

Don’t immediately delete the task.

Why:

- you lose evidence (XML, timing, user context)

- you might remove your best pivot for fleet-wide scoping

- some malware will recreate tasks, and you’ll miss the recreation pattern

Do this instead

1) Export/capture task details (XML if possible) 2) Identify the referenced payload path and hash it 3) Pull parent process lineage if available (who created it?) 4) Contain the host if the payload is clearly malicious 5) Hunt for the same task name/action pattern across the fleet

Delete later, after evidence is preserved and scope is known.

Mini exercise: “Is this task suspicious?”

Take three tasks from a workstation:

- one Windows default task

- one vendor updater task

- one suspicious task (real or lab-made)

For each, write down:

- action path (where does it execute from?)

- signer status of the action binary

- trigger style (logon/timer/idle)

- creation time (recent vs long-standing)

If you can’t confidently separate them today, you have a visibility or process gap—not a malware gap.

Artifact Annex (field notes)

What to capture

- Task name and folder path

- Creation time + user context

- Trigger(s)

- Action command + arguments

- Task XML (best)

High-signal suspicious patterns

- Actions pointing to:

C:\Users\*\Downloads\C:\Users\*\AppData\Roaming\C:\Users\*\AppData\Local\Temp\

- Use of:

rundll32.exewith DLL in user profilepowershell.exe -enc/ hidden window flagscmd.exe /claunching scripts or LOLBins

Detection ideas

- Alert on new scheduled task creation where action references user-writable paths

- Correlate task creation within minutes of suspicious download execution

- Hunt tasks with “Update/Health/Security” naming plus non-standard action paths

Closing thought

Scheduled tasks are not glamorous. They are not novel. They are not “advanced.”

And that’s exactly why they work.

Attackers don’t need exotic persistence when defenders aren’t consistently watching the simplest, most reliable mechanism in the OS.

If you make scheduled task creation and task actions visible—and you actively hunt the high-signal patterns—you remove one of the most common footholds loaders rely on.