Windows Endpoint Timeline Forensics — Rebuilding the Story from Artefacts

Good DFIR is really good storytelling backed by artefacts. This post breaks down how to reconstruct a Windows endpoint timeline using Prefetch, Amcache, Shimcache, SRUM, event logs, and more — so you can explain exactly what happened, and when.

When something goes wrong on a Windows endpoint — malware infection, suspicious admin activity, data theft — your job in DFIR is to rebuild the story:

- What executed?

- When did it start and stop?

- Which user and which process kicked it off?

- What files, registry keys, and network connections were involved?

You can’t answer these questions reliably with just one artefact. Instead, you build a timeline using multiple sources:

- Prefetch — what binaries executed and when.

- Amcache & Shimcache — evidence of execution and program installation.

- SRUM — application and network usage patterns.

- Windows Event Logs — process creation, logons, service changes, task scheduling.

- File system timestamps & registry keys — supporting context.

This post walks through the main Windows artefacts used for timeline forensics, how they behave, their caveats, and a practical workflow you can use to turn messy evidence into a clear narrative.

1. Why Timelines Matter in DFIR

Every investigation eventually turns into questions about time:

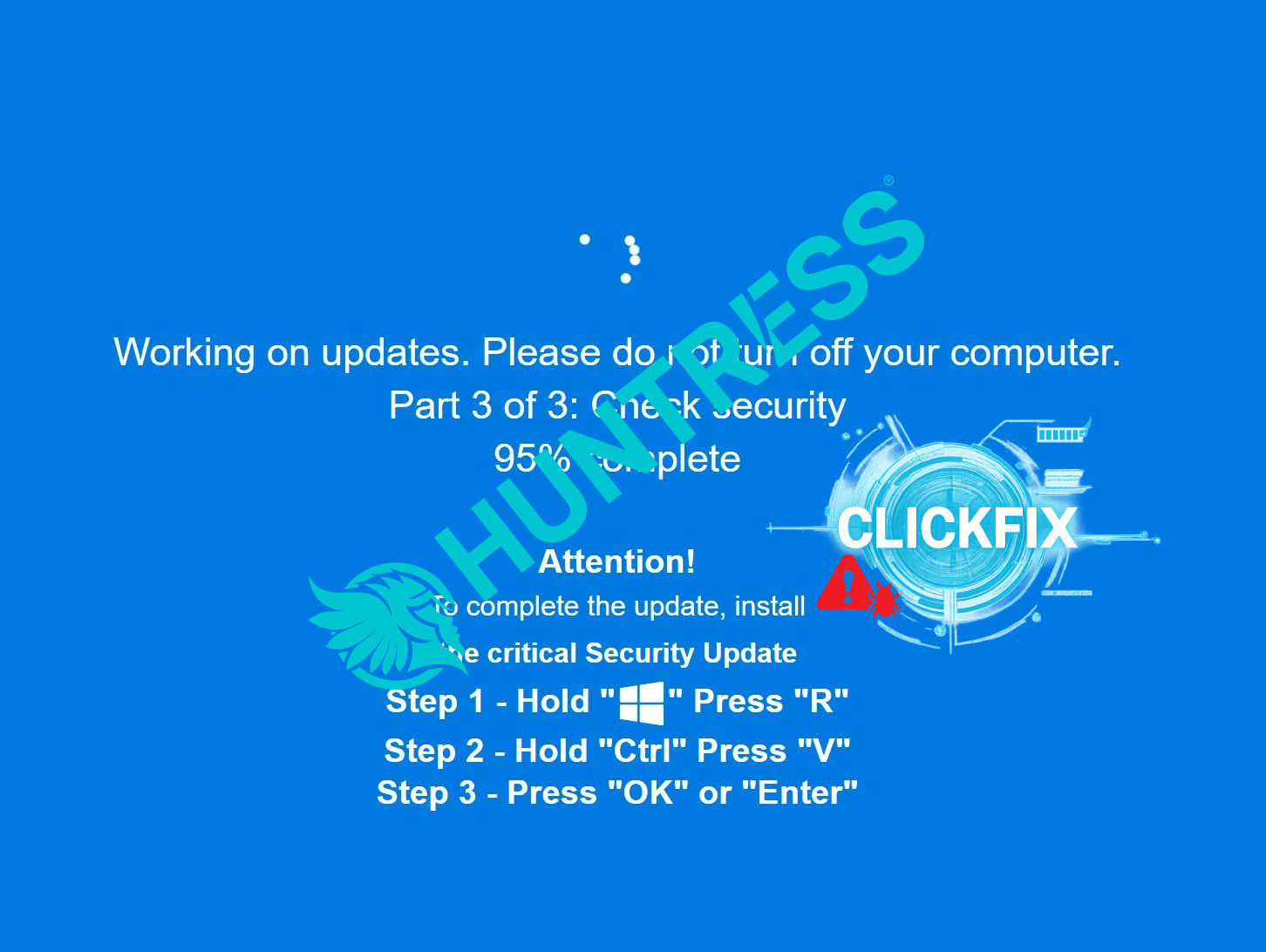

- Did malware run before or after the phishing email?

- Was the suspicious admin account created before or after the VPN login from a foreign IP?

- Did data exfiltration occur before encryption, or was it a pure smash-and-grab?

Timelines let you:

- Validate or disprove assumptions — was that binary actually executed, or just dropped?

- Sequence attacker actions — initial access → persistence → discovery → lateral movement → impact.

- Communicate clearly to non-technical stakeholders — a chronological narrative is easier to understand than a collection of IOCs.

On Windows endpoints, a good timeline is built by stacking artefacts from multiple subsystems so that, even if one is missing or tampered with, others still tell the story.

2. Acquisition and Time Normalisation

Before diving into artefacts, two critical basics.

2.1 Sound acquisition

Whenever possible, acquire:

- A full disk image (or at least a targeted collection of system and user directories).

- Relevant registry hives (

SYSTEM,SOFTWARE,SAM, NTUSER.DAT files). - Windows event logs (

.evtxfiles) fromC:\Windows\System32\winevt\Logs. - If supported, EDR telemetry exports (process/network logs).

You can use commercial suites, open-source tools, or frameworks like KAPE/Velociraptor to automate artefact collection — but the principle is the same: gather all potential time-bearing artefacts before making changes to the system.

2.2 Time normalisation

Windows stores timestamps in different formats and time zones:

- FILETIME (UTC) in NTFS metadata.

- Local time vs UTC in various registry keys and logs.

- Different tools rendering the same underlying time differently.

When building a timeline:

- Convert everything to UTC in your working dataset.

- Keep track of the system’s time zone and clock drift (e.g., via event logs, NTP settings).

- When reporting, you can translate back to local time, but your analysis should be consistent.

If you skip normalisation, you risk mis-ordering events around daylight savings changes, clock skew, or cross-region comparisons.

3. Prefetch — “What Ran, and When”

3.1 What Prefetch is

Prefetch files (.pf) are used by Windows to speed up application launches by caching information about the executable and the files it uses. For forensics, they provide:

- The executable path and name.

- File system paths the process accessed during startup.

- A run count (how many times it executed).

- Up to the last 8 execution timestamps (depending on OS version).

You’ll find them in:

C:\Windows\Prefetch

Note: Prefetch is enabled by default on workstations, but often disabled or limited on some servers.

3.2 How Prefetch helps timelines

For each suspicious binary, Prefetch can tell you:

- Whether it actually ran (presence of a

.pffile). - Roughly when it ran (the last run timestamp).

- How many times it ran (run count).

- Which other files it used on startup (useful for identifying dropped components).

Example use cases:

- Confirming that

invoice_viewer.exe(suspected loader) executed at 2025-10-12 08:14:32 UTC, matching a phishing email received 2 minutes earlier. - Seeing that the ransomware binary ran once and touched specific directories before encryption.

- Detecting that

powershell.exeseveral directories deep in user space has run 27 times in the last day.

3.3 Caveats

- Prefetch entries can be deleted, either manually or by cleaning tools.

- On busty systems, Prefetch has a maximum count; older entries roll off.

- Paths may be truncated, and understanding the full path sometimes requires context.

You should never rely on Prefetch alone — but it is an excellent starting point for “did it run?” questions.

4. Amcache and Shimcache — Evidence of Execution

4.1 Amcache (Amcache.hve)

Amcache is a registry hive used by Windows to track program executions and installations. The main file:

C:\Windows\AppCompat\Programs\Amcache.hve

Amcache stores:

- Full paths to executables.

- SHA-1 hashes (on newer systems).

- First execution time (approximate).

- File size and version information.

For timeline purposes, Amcache is valuable for:

- Identifying binaries that have been executed at least once.

- Correlating suspicious file paths with approximate introduction time.

- Linking artefacts across hosts via hashes.

4.2 Shimcache (AppCompatCache)

Shimcache (often referred to as AppCompatCache) is another execution-related artefact stored in the registry:

- On modern systems: under

SYSTEMhive,ControlSet001\Control\Session Manager\AppCompatCache(location can vary by version).

Shimcache typically records:

- Paths to executables and some DLLs.

- Flags indicating execution and cache usage.

- A timestamp (on some versions) related to last modification or first insert.

Shimcache is useful when:

- Prefetch is disabled or purged.

- You want an additional indicator that a file existed and was likely executed.

- You’re working with older events where other artefacts have rotated.

4.3 Caveats

- Neither Amcache nor Shimcache are perfect execution logs; they’re best treated as evidence of presence and likely execution.

- Timestamps can be noisy or missing, depending on OS version.

- Both can be tampered with by advanced attackers.

In timelines, use Amcache and Shimcache to support and cross-check Prefetch and event log data, not replace it.

5. SRUM — Application and Network Usage Patterns

5.1 What SRUM is

SRUM (System Resource Usage Monitor) collects periodic statistics on resource usage. Its database is located at:

C:\Windows\System32\sru\SRUDB.dat

SRUM tracks, among other things:

- App-level network usage over time.

- Battery and energy usage.

- Some per-user associations.

In DFIR, SRUM is gold when you need to know:

- Which process or app used the network during a specific time window.

- Whether a rarely used binary suddenly started transferring large amounts of data.

- Correlations between user logons and app activity.

5.2 Using SRUM in timelines

Because SRUM samples periodically, it’s less precise than per-event logging, but it can show patterns:

- During an exfil window, you might see

rclone.exewith unusual upload activity. - A previously unseen binary may suddenly show steady outbound usage during off-hours.

- Browser processes associated with a user may spike in usage during a credential theft campaign.

Combining SRUM entries (time-bucketed usage) with network and firewall logs gives you a cross-validated view of data movement.

5.3 Caveats

- SRUM has limited retention (days to weeks) depending on system configuration.

- Parsing SRUDB.dat requires specialised tools; it’s not human-readable by default.

- Time granularity is coarser than event logs; treat it as supporting evidence.

6. Windows Event Logs — The Structured Narrative

6.1 Key event logs for timeline work

While there are many logs, a core set covers most DFIR scenarios:

- System (

System.evtx) — service changes, device events, reboots. - Security (

Security.evtx) — logons/logoffs, object access, some process events (if enabled). - Application (

Application.evtx) — app-level errors and informational events. - Microsoft-Windows-Sysmon/Operational — if Sysmon is deployed, detailed process, file, registry, and network events.

- Additional logs like:

Microsoft-Windows-TaskScheduler/Operationalfor scheduled tasks.Microsoft-Windows-PowerShell/Operationalfor script block logging.Microsoft-Windows-Windows Defender/Operationalfor AV detections.

6.2 Event IDs you’ll use constantly

Some non-exhaustive examples:

- 4624 / 4625 — successful / failed logons.

- 4672 — special privileges assigned to new logon (e.g., admin tokens).

- 4688 — process creation (when enabled).

- 7045 — a service was installed.

- 4698 — a scheduled task was created.

- 4104 — PowerShell script block logging (if enabled).

- Sysmon 1 — process creation.

- Sysmon 3 — network connection.

- Sysmon 11 — file create; 13 — registry set.

Mapping these onto your timeline provides the backbone of “who did what with which process, and when”.

6.3 Caveats

- Verbosity vs retention: high-level logging reduces blind spots but can fill disks quickly if not tuned.

- Logs can be cleared; watch for 1102 (log cleared) events.

- You need to understand provider-specific quirks (e.g., local vs domain logons, service account patterns).

7. File System and Registry Timestamps

7.1 NTFS timestamps

Each NTFS file has multiple timestamps:

- $STANDARD_INFORMATION — creation, modified, MFT modified, accessed.

- $FILE_NAME — another set of timestamps tied to the directory entry.

Attackers sometimes rely on “timestomping” (editing timestamps), but in many real-world cases, you’ll still find:

- File creation times that align with malware drop events.

- MFT modification times that link to renames or moves.

- Access times (if enabled) that show when files were read.

7.2 Registry keys

Registry keys hold their own last write times. Relevant areas include:

Run/RunOncekeys for persistence.- Service definitions under

SYSTEM\CurrentControlSet\Services. AppCompatFlags,RecentDocs, shellbags, and more.

In timelines, these timestamps can:

- Confirm when a persistence mechanism was created.

- Help sequence installation vs first run of a program.

- Show user interaction with folders and files (via shellbags and recent items).

7.3 Caveats

- Timestamps can be manipulated, and some are updated by legitimate maintenance.

- Some artefacts only track last change, not history.

- Always interpret timestamps in context with other sources.

8. Building the Timeline: A Practical Workflow

Here’s a simple but effective workflow you can adapt, regardless of tooling.

8.1 Step 1 — Define your window and anchor events

Start with what you know:

- Alert time (e.g., AV detection, EDR alert, SOC ticket).

- User-reported time (“I opened the weird email around 9:15”).

- Obvious markers (system reboot, encryption start, service creation).

Define a window around these (e.g., -2 days to +2 days) to start your timeline.

8.2 Step 2 — Extract core artefacts

From your acquired data, extract:

- Prefetch metadata (tool-processed into CSV).

- Amcache and Shimcache entries.

- SRUM app/network usage for the period.

- Windows Event Logs (exported and normalised).

- Key registry hive timestamps and NTFS file metadata for suspicious paths.

Standardise time to UTC and unify into a single dataset (CSV, SQLite, or a timeline tool of your choice).

8.3 Step 3 — Build an initial “spine” from event logs

Using Security/Sysmon logs:

- Plot logons, process creations, service and task creations, and script executions in time.

- Mark which user accounts and SIDs are involved.

- Note any log clears or suspicious gaps.

This forms the spine of your timeline — the primary narrative of who did what.

8.4 Step 4 — Enrich with Prefetch, Amcache, Shimcache

Overlay:

- Prefetch last-run times for any binaries of interest.

- Amcache first-seen times for those binaries.

- Shimcache entries corroborating presence and likely execution.

You might discover:

- Executions that didn’t log in event logs (logging disabled or incomplete).

- Binaries that executed before your initial window, indicating earlier compromise.

8.5 Step 5 — Add SRUM and network context

Bring in:

- SRUM app/network usage to show which processes were active around key events.

- Firewall, proxy, or EDR network logs to show destinations and volume.

This helps you see:

- Whether suspicious binaries made outbound connections and how intense they were.

- Whether data exfiltration overlapped with particular processes or times.

8.6 Step 6 — Refine, iterate, and narrate

As patterns emerge:

- Narrow or widen your time window if needed.

- Validate hypotheses (e.g., “Did Mispadu install before the user’s banking session?”).

- Remove irrelevant noise so your final timeline focuses on attack-relevant actions.

Finally, write the narrative in plain language, supported by the artefact-backed timeline:

At 08:14 UTC, user X opened

Invoice_2025.pdffrom email Y. Within seconds,WINWORD.EXEspawnedwscript.exe, which launchedinvoice_viewer.exefrom the Downloads folder. Prefetch and Amcache confirminvoice_viewer.exeexecuted at least twice that morning…

This is the output that management, legal, and other teams can actually use.

9. Common Pitfalls in Windows Timeline Forensics

Even experienced analysts get caught by:

- Over-focusing on one artefact — trusting Prefetch or AppCompatCache without cross-checking.

- Ignoring time zone and clock drift — leading to mis-ordered events.

- Assuming log completeness — forgetting that logging might have been disabled, misconfigured, or tampered with.

- Not capturing enough — doing a quick triage that misses critical hives or logs, forcing you to revisit the host later (if it still exists).

The cure is always the same: collect broadly, normalise carefully, and cross-validate.

10. Bringing It All Together

Windows endpoint timeline forensics is less about memorising every obscure artefact and more about combining the right ones in a structured way.

If you:

- Understand what Prefetch, Amcache, Shimcache, SRUM, event logs, and NTFS/registry timestamps can and can’t tell you.

- Normalise times and correlate events across sources.

- Build timelines that answer concrete investigative questions…

…then you can turn a noisy, confusing endpoint into a clear, defensible story of compromise and response.

The next time an alert lands on your desk:

- Anchor your timeline in a small window.

- Pull in the artefacts above.

- Iterate until the story makes sense.

Over time, these steps become muscle memory — and you’ll find that Windows endpoints, no matter how messy, tell remarkably consistent stories when you know how to listen to them.